Designs by Gio Ponti and Raymond Loewy were once as close as your local jeweler. Now they’re even closer.

One of the most difficult areas in Mid-Century collecting is flatware: the famous patterns like Dansk’s “Fjord” are priced to the heavens, and lesser-known designs like those from the manufacturer Stanley Roberts are often hard to assemble into complete services. There is a way to have top-quality modernism from very famous designers at reasonable prices, and it’s found in a direction most collectors never think of taking: American sterling silver. Once the most expensive and luxurious of all metals commonly used for flatware, silver’s price has dropped so low that sterling can be less than half the price of stainless like “Fjord” or Arne Jacobsen’s “AJ”. It’s also much easier to care for than most people have any idea.

American modernist sterling began with an odd circumstance stemming from the end of World War II. Vast quantities of silver had been stockpiled for the war effort- many electronics of the era depended on it. When hostilities ceased, the stockpile was no longer needed, and was released to the open market at favorable prices. Makers of table silver seized the opportunity gladly, eager to market their product more broadly than ever before to consumers flush with savings; there had been little to spend wartime earnings on, and American bank accounts were bulging. The result was a huge silver industry push to get sterling flatware and holloware into homes that had never aspired to such luxe before. Arbiters of public taste like etiquette expert Emily Post were enlisted to let hoi polloi know that sterling, and only sterling, was the wedding gift of choice. Post’s rival, Amy Vanderbilt, went so far as to warn brides that an insistence on sterling gifts from friends was the only prudent thing to do: “If you don’t get your sterling now,” she warned, “you may never get it.”

Most sterling, of course, was in traditional designs, many of which had been in production for decades. But a new sensibility was emerging: the Art Deco designs of French silversmith Jean Puiforcat had influenced American manufacturers in the direction of simplicity. Gorham’s “Hunt Club”, introduced in 1931, was a first step, using a stylized palmette motif in Hollywood Moderne fashion. But true modernism was not to be seen in mass-market silver until 1948, and it arrived with a bang - Towle’s “Contour”. Exactly right for the mood of the late 1940’s, the pattern was fresh, new, like nothing ever seen before, and yet available in all the old familiar formally-oriented pieces, including holloware like coffee pots. Designed by John O. Van Koert, the sleek, biomorphic shapes of “Contour” were an instant hit; a bride could declare her allegiance to the future, yet reassure herself that the values of the past were still important.

“Contour” had little competition for a time, although Gorham tried with a 1954 pattern called “Theme”, which was decently well-designed, and a 1956 design named “Celeste”, which wasn’t. There was also a 1953 International Silver design known as “Silver Rhythm”, but the real turning point for modernist sterling came in 1957, with a pair of near-twins- Gorham’s “Stardust” and Wallace’s “Discovery”. Heavily copied in everything from quality stainless to 10-cent Woolworth’s chrome-plate, “Stardust” featured a motif of scattered starbursts on its handle, where “Discovery’s” pattern was seed-like. While they were roughly similar in appearance, their pedigrees were highly divergent. “Stardust” was done by a design team at Gorham whose members are not known, but “Discovery” was by no less than Raymond Loewy. Consumer acceptance of both was excellent, although “Stardust” seems to have sold more strongly, due to Gorham’s heavier advertising. Modernism was now a mainstream taste in sterling, and the next year, 1958, would be the beginning of palmy days.

THE BEGINNING: Towle’s Contour (1) was the first genuinely modern mass-produced sterling. Gorham’s Theme (2) was another early step in the direction of simplicity, but the company’s Celeste design (3) was a pseudo-modern riff on old floral themes. International Silver’s Silver Rhythm (4) was another early 1950s modern design. (Image Credit: © 1998-2003 Replacements, Ltd. Used by permission.)

MODERNISM GOES MAINSTREAM: Gorham’s Stardust (1) was a favorite of young brides in 1957. The lesser-known Discovery from Wallace (2) was from the design atelier of Raymond Loewy. (Image Credit: © 1998-2003 Replacements, Ltd. Used by permission.)

The most esteemed maker of American sterling, Reed & Barton, was coming late to modernist design, but it entered the market with a pattern of the highest design quality: “The Diamond” - or, as it was popularly referred to, just “Diamond”. Done under the auspices of R&B’s Director of Design, Danish-trained John Prip, “Diamond” began as a series of concept sketches commissioned from Gio Ponti. The Ponti sketches, based on the architect-designer’s favored diamond theme also used in his famous Pirelli Building, were beautiful, but Prip’s intensive training in practical matters of production told him that they were not going to be producible as drawn. Prip assigned R&B staffer Robert Ramp to work on the production aspects of the project, which included both a full line of flatware and holloware. By 1958, sterling holloware was not much in demand, due to high cost, but R&B’s “old money” customer expected to be served across the board. Uncommonly heavy, with an exceedingly luxurious feel and staggeringly perfect finish, “Diamond” was thesterling for those who liked their modernism to be top-of-the-line.

THE PONTI NO ONE KNOWS: Gio Ponti originated Reed & Barton’s highly successful 1958 pattern, The Diamond. R&B staffer Robert Ramp engineered the design for production under the direction of John Prip. (Image Credit: © 1998-2003 Replacements, Ltd. Used by permission.)

SUCCESS FOLLOWS SUCCESS: Kirk Stieff’s Signet (1), Lunt’s Raindrop (2), Gorham’s Firelight (3), Reed & Barton’s Lark and Dimension (4, 5), and Towle’s Vespera (6) were designs that followed the success of The Diamond. Gorham’s Classique (7) was quite similar to The Diamond, offering much the same look in a lighter weight, at a lower price. (Image Credit: © 1998-2003 Replacements, Ltd. Used by permission.)

Despite its cost, “Diamond” was a big seller, being the freshest, most distinctive design available, and its success inspired other manufacturers to get with the times, fast. Kirk Stieff weighed in with 1958’s “Signet”, and by 1959, Lunt had entered the market with its timeless, if somewhat lightweight, “Raindrop”. That same year also saw the introduction of Gorham’s “Firelight”, and in the new decade of the Sixties the stream of modernist sterling became a minor torrent. R&B’s John Prip came up with two designs more popularly priced than “Diamond”, his 1960 “Lark” and 1961’s “Dimension”. Towle brought out a pattern called “Vespera” in 1961, and that same year, Gorham designer Donald Colflesh decided to compete with “Diamond” on the most direct terms possible, imitation. His “Classique” was remarkably similar to the Ponti / Ramp design, but in a somewhat lighter, more affordable weight. Gorham also adopted a new marketing strategy for “Classique”- the pieces available were based on actual consumer preference, not outdated lists of what had always been offered. Banished were seldom-ordered pieces like fish knives and forks, and included were new “casual living” pieces like salad servers made of olive wood with sterling handles.

1961 also was the year that one of the most famous of all modernist patterns was put on the market - International Silver’s breathtakingly simple and beautiful “Vision”, still in production today. By 1962, the most famous producer of modernist tabletop, Dansk, was offering its own sterling pattern, designed by the company’s chief designer, Jens H. Quistgaard. Called “Tjorn”, it was a big departure for a company devoted to informal modernism; with the introduction of the pattern, Dansk entered the big time, able to compete with purveyors of traditional designs line-for-line, able to serve the wealthiest bride as well as any manufacturer. All these early 1960s patterns were modernist in the strictest sense, depending on exquisite line and superb surface development, and 1963 was the year of the very handsome Gorham pattern, “Esprit”. But by 1964, ornament reared its ugly head again; that year saw surface work applied to the formerly pristine “Classique”, resulting in a new Gorham pattern called “Damascene”. Suddenly surface work was all the rage; evidently some fans of The Latest Thing wanted their modernism warmed up a little.

YESTERDAY’S VISION - AND TODAY’S: International Silver’s Vision is still in production. Seemingly simple, the design’s shape is so complex that no single photograph can capture it; three views are shown here. (Image Credit: © 1998-2003 Replacements, Ltd. Used by permission.)

SCANDINAVIAN SIMPLICITY: Modernism was nothing new at Dansk Designs, but sterling silver didn’t enter the line until 1962, when Tjorn was introduced. (Image Credit: © 1998-2003 Replacements, Ltd. Used by permission.)

The trend continued; 1965 brought Wallace’s “Royal Satin” and Towle’s “R.S.V.P.”. Gorham’s “Esprit” was offered in two new decorative variations that were not really modernist at all, 1965’s “Gossamer” and 1966’s “White Paisley”. By 1967, John Prip’s latest for R&B, “Cellini”, had a florentine-finish handle (R&B’s “Cellini” is not to be confused with an older, non-modernist Gorham pattern of the same name). That same year, Prip’s “Diadem” was accented with a band of that most traditional silver ornamentation, beading, used in a new way. By 1969, designs had become decadent, with Oneida’s “Rubaiyat” showing just how far off-message modernism had become, and by 1970, it was really all over, with traditional patterns re-gaining lost ground of consumer acceptance. It had been a very interesting two decades, and we will probably never see anything like their burst of creativity again in mass-market silver manufacture.

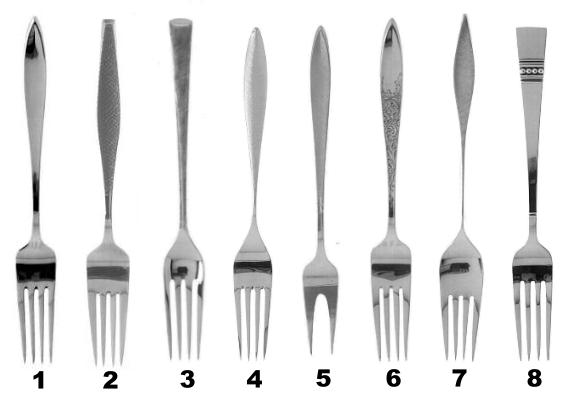

DRIFTING AWAY: Gorham’s Esprit (1) was simplicity itself, but the company applied a cross-hatched decoration to the formerly pristine Classique to produce Damascene (2). Surface work also figured in Wallace’s Royal Satin (3) and Towle’s R.S.V.P. (4). Esprit was also the basis for two non-modernist variations, the florentined Gossamer (5; lemon fork shown), and White Paisley (6) with a traditional figure. Reed & Barton’s John Prip also began using surface work in his florentined Cellini (7) and his beaded Diadem (8). (Image Credit: © 1998-2003 Replacements, Ltd. Used by permission.)

THE END OF AN ERA: A close look at Oneida’s Rubaiyat shows that the overall shape is Scandinavian, but the handle’s heavy relief and piercing show that consumer taste had turned away from genuine modernism. (Image Credit: © 1998-2003 Replacements, Ltd. Used by permission.)

Today, modernist sterling lurks everywhere; those wedding gifts of the Fifties and Sixties turn up for sale all the time. Complete sets are not uncommon, both at online auctions and in estate sales. Expect to pay roughly $100 a place for most patterns in good, unscratched condition; “Diamond” often goes for more, due to the heavy weight that tells even ignorant sellers the pattern is extra-quality. There are ways to save money off even today’s low prices; antique fairs and flea markets often have a booth whose owner sells odd pieces of sterling at $7-10 per piece. Some combing and patience can pay big dividends here; a recent check of such a table piled high with unlovely-looking silver unearthed nine place pieces of Gorham’s “Classique” and a “Diamond” slotted serving spoon. The total was $70 for all ten pieces - much less than the price of one Dansk “Fjord” serving piece. Pieces that are scratched or bent are very often salvageable; almost every jeweler does minor silver repair or can refer you to someone who does it. If bargain-hunting does not yield a complete service of every piece you’d like to have, replacement services like Replacements, Ltd. ™ can fill in what’s missing. While replacement services’ pricing can be higher than that of other sources, the condition of their merchandise is perfect, their selection is very comprehensive, and their prices include the costs of extra services not found elsewhere. Replacement service silver will nearly always be in far better condition than anything you can find on your own - the extra cost is worth it for the choosy owner, or for that hard-to-find piece that just doesn’t turn up very often.

Now you know the best-kept secret in all of modern collectible design- there is modern silverware out there at good prices, with a nearly endless supply of replacement pieces. All you have to remember is one word- silver.

CARING FOR YOUR MODERN STERLING

Sterling has a bad rap - most people believe it has to be polished constantly. It’s simply not true; with proper use and care, you’ll have to polish no oftener than once or twice a year. Here are the basics; some tactics for dealing with damage follow:

Use your silver as often as possible, preferably every day. Constant handling and proper washing remove contaminants from the surface of the silver, making tarnish less likely to occur. If you have more place settings than family members, rotate the settings used, to even out the wear and to extend the benefits of handling to all your pieces.

Hand-wash, then dry right away. Use the hottest water your hands are comfortable with; never use lemon or citrus-scented detergent, which is acidic. Also don’t use cleaners with chlorides. Wash and rinse in hot water, then dry immediately, to prevent water spotting. Never soak sterling; this can loosen knife handles and can roughen the silver’s surface.

Sorry, no dishwasher! The heat and chemicals used in machine dishwashing are murder on sterling. You’ll get away with it a few times, then you’ll start to notice a whitish haze on your flatware caused by alkali in the detergent. This is very difficult to remove, often requiring professional attention. It’s also possible to get black spots on the silver if any stainless steel comes in contact with it during the wash cycle, due to an electrolytic reaction between the two dissimilar metals. Worst of all, the heat in a dishwasher can loosen the cement that fastens knife blades to their handles, or even make the cement expand, bursting the handle along its soldered seams. Don’t risk it.

Protect between uses. It’s easy to keep air-borne contaminants away from silver; just pop a few 3M ® anti-tarnish strips into your flatware drawer, and change them periodically. If you’d rather, a drawer can be lined in Pacific Silvercloth ™, which will also keep tarnish at bay. Silver chests are lined in this material, too. If you can arrange it, it’s better to store silver in rows, laying each piece on its side, rather than stacking. This minimizes scratching. For long-term storage, Ziploc ™ bags are great, but never use plastic wrap. It can bond itself to silver, requiring professional removal. Never use a rubber band around silver; it will leave black tarnish wherever it touches.

No silver dips. Ever. These products work by a chemical action that is hard on your silver, and can cause damage if left on too long. They’re also capable of soaking into knife handles and hollow parts like teapot feet, creating expensive problems.

Sometimes, damage occurs in spite of everything you do, or perhaps you’ve found some sterling that has been neglected. Here’s how to make blackened, scratched, and damaged silver look great again:

Use a rouge-based polish to remove deep tarnish and light scratches. My preference here is Wenol ™, a German polish available at Williams-Sonoma and many hardware and kitchenware stores. The name is pronounced VEE-knoll. Simichrome ™ is pretty much the same thing. Both these polishes are capable of bringing up a deep luster on silver. They’re too abrasive for regular polishing; use them only once, for restoration purposes. Polish using a soft cotton cloth, and wash the silver after polishing, to remove polish residue. If you don’t want to deal with dark tarnish yourself, professional re-polishing is only $2-3 per piece.

Re-polish, using a silver polish. I like Wright’s Silver Cream ™, which brings up a bright shine. Follow the directions on the container. There’s nothing toxic in Wright’s, so wiping all the polish off the silver is all that’s needed- no need to re-wash. You may prefer a different product; just follow directions, and you’ll be fine.

If all else fails, call in the pros. If you’ve never owned silver, you’re in for a pleasant surprise: Unlike stainless, damage to sterling can usually be repaired. Jewelers and silversmiths can re-buff sterling to a like-new luster. They can straighten pieces bent in the disposall. They can even replace a broken knife blade. If you send a piece of sterling in for repair, be sure to send an identical piece in perfect shape to give the craftsman something to match his repair to. Do get an estimate before the repair is done; sometimes it’s cheaper to buy a new piece, especially at today’s prices.

Advanced Ownership

Some people need, or like, pieces that were never produced in their preferred pattern. One of the biggest secrets among sterling collectors is that pieces can be converted and adapted to make nearly anything you want. Teaspoons can be re-shaped to produce orange spoons. Serving spoons can be pierced to make them slotted. Knives can be shorn of their blades, and the sterling handle used for pieces like asparagus servers, fish slices, candle snuffers, and punch ladles. Knives can also have their blades replaced with ones in different shapes, like the special blade seen on fish knives. As long as these conversions are done by a qualified silversmith, they’re legitimate items in their own right.

One Last, Little-Known Tip:

It’s possible to buy pieces of patterns that are officially discontinued, brand-new. Most manufacturers have a special-request program, where they take requests for pieces in patterns no longer in their regular line. If demand is sufficient, the manufacturer will break out the dies for the pattern, and make enough new pieces to fill requests. R&B’s “Diamond” still can be obtained this way, and your silver retailer may be able to advise you on other patterns. Not all patterns are available this way; if there has been no demand for a very long time, the dies may have been destroyed. Also, dies wear out, and most discontinued patterns never achieve enough demand to warrant the expense of making new dies.

The author and Jetsetmodern wish to extend special thanks to Liam Sullivan of Replacements, Ltd., for his invaluable assistance with picture permissions, and to Rachael Potts of Replacements, Ltd., for providing the images. Visit the Replacements, Ltd. website at www.replacements.com.

SOURCES

The Website of Replacements, Ltd., www.replacements.com

Telephone interview with John Prip, June, 1998.

Emily Post’s Etiquette, by Emily Price Post. Funk and Wagnalls, New York, various editions.

Amy Vanderbilt’s New Complete Book of Etiquette, by Amy Vanderbilt. Doubleday, New York, 1962.

TRADEMARK / COPYRIGHT NOTICES

All photographs used in this article are © copyright 1998-2003 by Replacements, Ltd., Greensboro, NC. Used by permission of the copyright holder.

Dansk ®, Fjord ®, and Tjorn ® are trademarks of Lenox, Inc., a division of Brown-Forman Industries.

Reed & Barton ™, Diamond ®, Lark ®, Dimension ®, Cellini ®, and Diadem ® are trademarks of Reed & Barton Silversmiths.

International Silver ™ , Silver Rhythm ®, and Vision ® are trademarks of The International Silver Company.

Oneida ™, Vivant ®, and Rubaiyat ® are trademarks of Oneida, Inc.

Wallace ™, Royal Satin ®, and Discovery ® are trademarks of Wallace Silversmiths, Inc.

Kirk Stieff ™ and Signet ® are trademarks of Kirk Stieff.

Lunt ™ and Raindrop ® are trademarks of Lunt Silversmiths.

Gorham ™, Hunt Club ®, Classique ®, Damascene ®, Stardust ®, Esprit ®, Gossamer ®, White Paisley ®,

Firelight ®, Theme ®, and Celeste ® are trademarks of Gorham Silver, Inc.

Towle ™ no longer exists as an actual manufacturer; certain classic Towle designs are produced under license by other silver manufacturers. Contour, Vespera, and R.S.V.P. are not among them.

All other trademarks designated by ™ and ® in this article are the property of their respective trademark owners.

The Secret is Out : American Modernist Sterling

Copyright © 2003 D.A. "Sandy" McLendon and Joe Kunkel, www.jetsetmodern.com Jetset - Designs for Modern Living. All rights reserved worldwide. This article may not be reproduced, reprinted, reposted or rewritten without express permission in writing from the author and publisher. First posted to the Web on July 8, 2003.